FCWWBDNITHBR: The Crane Wife

Today on Fictional Characters Who Would Be Dead Now If They Had Been Real I'm going to try something a little different. Previous entries in this series (which can be found here) have focussed on characters in novels; today, we review a character from myth and song. It's gonna get all bardic up in here.

The Crane Wife is both a Japanese folktale and the title of The Demberists' 2006 album. I will consult the text of emponymous songs of the indie-prog-folk record, and the substance of the Japanese legend. Today, because I've been thinking about it since Gonzales v. Carhart, we'll touch on feminism, and women's roles as productive and reproductive members of the household. Yeah, I know, it's gonna be super exciting.

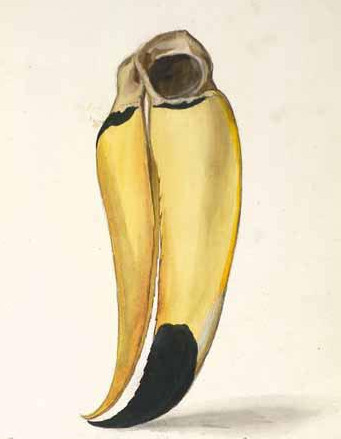

The story begins when a peasant is out in the woods one snowy evening. He finds wounded crane, an arrow has pierced its wings. Overcome with pity for the beautiful bird, he takes the crane home and nurses it back to health. After it is strong enough, the peasant takes the bird back to the woods and releases it. The bird flies away and the poor man walks home in the snow. The next day a beautiful woman comes to the peasant's cottage. He welcomes her and serves her some meager food and falls in love. They marry and she moves into his cottage. Realizing that household finances are very low and that they might not survive the harsh winter, the wife volunteers to weave silk cloth for sail at the village market. She goes behind a screen and begins her work, warning her husband that he mustn't watch her while she weaves. The husband obeys and every day the wife comes out with a magnificent new garment of brightly colored silk. What the husband does not notice is that every day, the wife's health grows worse and worse.

But by now the money brought into their meager household by the wife's textiles has made them rich merchants. The peasant's greed has become too much to bear and he sneaks into the cottage and behind the screen to see his wife at her work so that he can learn her secrets. He sees, to his shock and horror, a crane--the same crane he found in the forest bleeding on the snow--plucking out its feathers and weaving them into cloth. The crane flew out of the house and into the night and the peasant never saw his wife again. Or, as per the song:

So what are we to make of the fable of The Crane Wife; and more important to the mission of FCWWBDNITHBR, what can we learn from The Crane Wife herself?

I think the first place to look is the intersection of women's work and women's property in traditional societies.

The Crane Wife joins the peasant and forms a household out of gratitude. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that the peasant's generosity toward the crane caused her to fall in love. And once a wife she had to contribute to the household. Women's work, the Crane Wife's work is work of the body, it is reproductive, not productive. The husband alienates his labor for income wither in monies or in kind or in reciprocal obligation. His efforts are given away with the expectation of a return that will contribute to house holdings. But the wife is different. Her role is internal to the household and therefore necessarily confers less status. She does not alienate her labor, but rather is in charge of maintaining the household and associated property. Her only asset is herself. And her only social capital is through her husband. Her source of contribution and capital is her body and her most important contribution is the fruit of her body either in children or her role as "manager" to her husband's "owner."

So too The Crane Wife. She contributes through her own body. Her work is not external to the home and thus productive of new resources, but rather internal and reproductive of her self. She recapitulates her marriage every time she makes a new garment by re-sublimating her "true" crane self and instead presenting a thing of beauty and cementing a relationship founded on the suffering of the "true" crane self.

And the lesson. When the peasant man oversteps his bounds, when he seeks to intrude on her feminine sphere, appropriate reproductive resources, and usurp her only source of independent identity within the household, then the spell is broken. The marriage, that is, is broken. And why the resonance with Carhart? Because the privacy of a woman's body and her right to use it as she pleases, to make her own decisions about it--even when it implicates the structure of the whole family--and it's health are among the most ancient rights of civilization and when you (or, say, five old-ass supreme court justices) impinge on that freedom you break one of the basic rules about women: women are in charge of that shit for themselves and nobody else. Appeals to tradition to limit the rights of women to control their bodies are so much hokum--no different than appeals to the tradition of college fraternities, they are "traditions" established by the bourgeoisie in the Victorian era to reinforce more status conscious economic relationships between the sexes.

Basically, the peasant fucked up in the same way that we are currently fucking up here in 21st Century America. His basic assumption was that she, The Crane Wife, as a woman was not competent to make decisions for herself, and instead he had to monitor her activities either for her protection or to gratify his prerogative as the man of the house. This is all rubbish because women are in fact people. And they get to make their own decisions.

The Crane Wife is both a Japanese folktale and the title of The Demberists' 2006 album. I will consult the text of emponymous songs of the indie-prog-folk record, and the substance of the Japanese legend. Today, because I've been thinking about it since Gonzales v. Carhart, we'll touch on feminism, and women's roles as productive and reproductive members of the household. Yeah, I know, it's gonna be super exciting.

The story begins when a peasant is out in the woods one snowy evening. He finds wounded crane, an arrow has pierced its wings. Overcome with pity for the beautiful bird, he takes the crane home and nurses it back to health. After it is strong enough, the peasant takes the bird back to the woods and releases it. The bird flies away and the poor man walks home in the snow. The next day a beautiful woman comes to the peasant's cottage. He welcomes her and serves her some meager food and falls in love. They marry and she moves into his cottage. Realizing that household finances are very low and that they might not survive the harsh winter, the wife volunteers to weave silk cloth for sail at the village market. She goes behind a screen and begins her work, warning her husband that he mustn't watch her while she weaves. The husband obeys and every day the wife comes out with a magnificent new garment of brightly colored silk. What the husband does not notice is that every day, the wife's health grows worse and worse.

But by now the money brought into their meager household by the wife's textiles has made them rich merchants. The peasant's greed has become too much to bear and he sneaks into the cottage and behind the screen to see his wife at her work so that he can learn her secrets. He sees, to his shock and horror, a crane--the same crane he found in the forest bleeding on the snow--plucking out its feathers and weaving them into cloth. The crane flew out of the house and into the night and the peasant never saw his wife again. Or, as per the song:

So what are we to make of the fable of The Crane Wife; and more important to the mission of FCWWBDNITHBR, what can we learn from The Crane Wife herself?

I think the first place to look is the intersection of women's work and women's property in traditional societies.

The Crane Wife joins the peasant and forms a household out of gratitude. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that the peasant's generosity toward the crane caused her to fall in love. And once a wife she had to contribute to the household. Women's work, the Crane Wife's work is work of the body, it is reproductive, not productive. The husband alienates his labor for income wither in monies or in kind or in reciprocal obligation. His efforts are given away with the expectation of a return that will contribute to house holdings. But the wife is different. Her role is internal to the household and therefore necessarily confers less status. She does not alienate her labor, but rather is in charge of maintaining the household and associated property. Her only asset is herself. And her only social capital is through her husband. Her source of contribution and capital is her body and her most important contribution is the fruit of her body either in children or her role as "manager" to her husband's "owner."

So too The Crane Wife. She contributes through her own body. Her work is not external to the home and thus productive of new resources, but rather internal and reproductive of her self. She recapitulates her marriage every time she makes a new garment by re-sublimating her "true" crane self and instead presenting a thing of beauty and cementing a relationship founded on the suffering of the "true" crane self.

And the lesson. When the peasant man oversteps his bounds, when he seeks to intrude on her feminine sphere, appropriate reproductive resources, and usurp her only source of independent identity within the household, then the spell is broken. The marriage, that is, is broken. And why the resonance with Carhart? Because the privacy of a woman's body and her right to use it as she pleases, to make her own decisions about it--even when it implicates the structure of the whole family--and it's health are among the most ancient rights of civilization and when you (or, say, five old-ass supreme court justices) impinge on that freedom you break one of the basic rules about women: women are in charge of that shit for themselves and nobody else. Appeals to tradition to limit the rights of women to control their bodies are so much hokum--no different than appeals to the tradition of college fraternities, they are "traditions" established by the bourgeoisie in the Victorian era to reinforce more status conscious economic relationships between the sexes.

Basically, the peasant fucked up in the same way that we are currently fucking up here in 21st Century America. His basic assumption was that she, The Crane Wife, as a woman was not competent to make decisions for herself, and instead he had to monitor her activities either for her protection or to gratify his prerogative as the man of the house. This is all rubbish because women are in fact people. And they get to make their own decisions.

Labels: FCWWBDNITHBR, feminism, literature, music

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home